Chancel Repair Liability - The Background

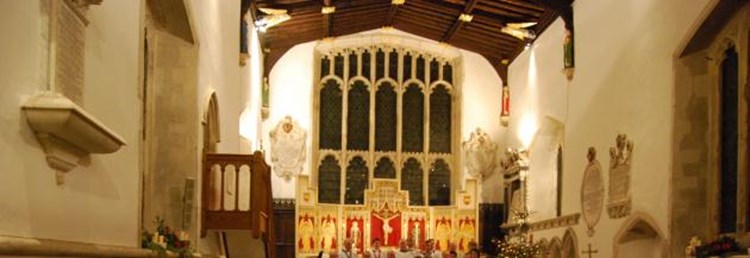

Some years ago there was a news article about some farm owners in Aston Cantwell, Warwickshire, who had fallen foul of a centuries old system known as Chancel Repair Liability (CRL). It seems the local church needed to carry out some urgent repairs to their chancel (generally the east end of a church beyond the crossing and containing the high altar, often separated from the body of the church by a rood screen) and had successfully applied for a grant from English Heritage to do so. However part of the grant making process is to ensure that there are no alternative sources of funding, and in this village there was a belief that the owner of a local field was responsible for all chancel repairs. A quick investigation established this to be the case, to the great detriment of the farm owners. So what had happened?

Well, we can blame it on King Henry VIII. First he broke from the Church of Rome and established the Church of England as a result of the process annulling his marriage to Catherine of Aragon which had produced no male heirs. This caused a general estrangement from mainland Europe and England was soon at war with France and Henry in desperate need of money to finance it. Apart from the king, the richest organization in the land was the Church and realizing this the king set in train the process known as the dissolution of the monasteries which effectively stole much of the wealth of the church including its lands and put it at the disposal of the king. Some of the income from the land was used to finance the crown and its wars, and some of the land was given away to the king’s associates as a means of maintaining their loyalty.

Now leaving aside the dubious morality both of the Church having such wealth and the crown taking it, this led to a bit of a problem. The Church used the revenues from its lands to finance itself and its charitable works. (One could argue that a similar principle continues today with local authorities raising finance based on land through the community charge.) One of the uses for this money was the upkeep of the chancel of local parish churches, which is where the priest carried out his regular religious duties. (The understanding was that the local population financed the upkeep of the rest of the church, ‘their bit’.) Even an absolute monarch like Henry VIII cannot afford to upset his subjects too much, and the population were already unhappy about having been excommunicated by the Pope. Henry obviously did not want them further worried by the sight of their church chancel crumbling to ruins, and when he gave away church lands they were given with the stipulation that the new landowner was still responsible for the maintenance of the local chancel in a wind and watertight condition.

For a couple of centuries this worked well. Everybody knew what the position was, and generally wealthy families retained the affected land. Then as time wore on bits of land were sold and things started to get confused. Different categories of former church land started to be a problem, some common, some subject to special tithes, some paying rents (not necessarily to the local church) some in the hands of city institutions, Oxbridge colleges and of course still the crown. So in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries parliament passed a series of acts designed to extinguish the archaic system of tithing and generally tidy things up. They succeeded in their objective with tithes (which were a serious problem) but chancel repair liability only received a few unhelpful mentions and remained on the statute book. In their work though, the Tithe Redemption Commission produced a comprehensive record of church lands in their record of ascertainments and this was often backed up by a huge and well executed set of tithe maps on parchment of affected parishes. For nearly a century things went quiet and it appeared that Chancel Repair Liability would wither away in growing ignorance.